When each day brings more news than we are used to seeing in a week, and the kind of news that only the most catastrophic imagination can accommodate, we find ourselves talking about the Reichstag fire. Time feels both accelerated and slowed down, and so we imagine that we have been talking about the fire for years. It is the new president’s new clothes: invisible, yet always present in our perception of him.

The Reichstag fire, it goes almost without saying, will be a terrorist attack, and it will mark our sudden, obvious, and irreversible descent into autocracy. Here is what it looks like: On a sunny morning you turn on the television as you make coffee, or the speaker in your shower streams the news, or the radio comes on when you turn the ignition key in your car. The voices of the newscasters are familiar, but their pitch is altered, and they speak with a peculiar haste. Something horrible has happened—it is not yet clear what—and thousands are dead, and more are expected to die. You hear the word “terror.” You feel it.

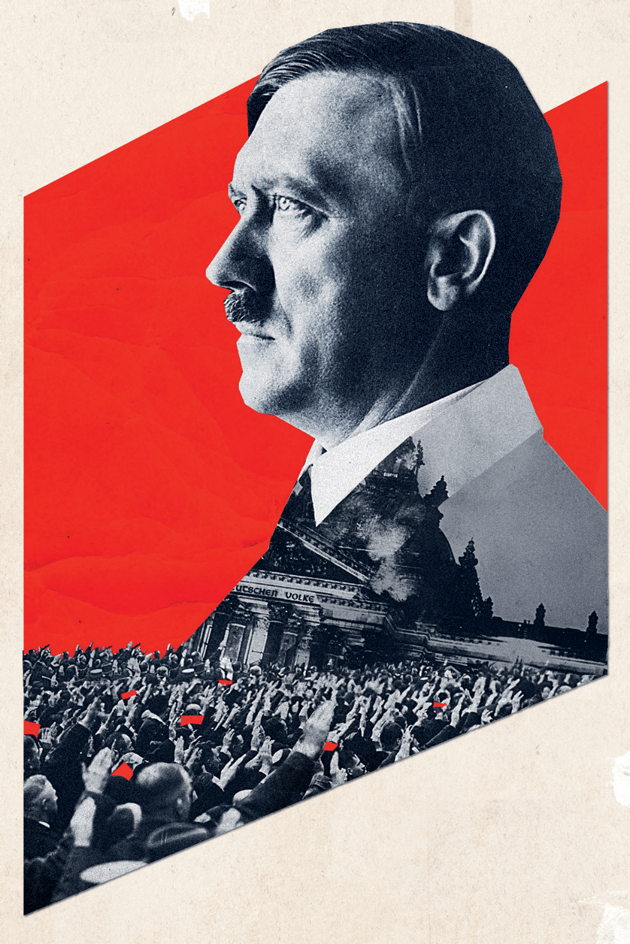

Illustrations by Lincoln Agnew. Source photographs: Adolf Hitler © Hulton Archive/Getty Images; crowd saluting Hitler © Visual Studies Workshop/Getty Images

You reach for your cell phone, but the circuits are busy, and will be for hours—it will take you the rest of the day to check in with your loved ones. They are safe, but changed. And so are you. So are all of us. Tragedy has cast its shadow over every space where you encounter strangers: the subway, your child’s school, your lunch spot. People are quieter, less frivolous, yet they are not subdued. They share a sense of purpose that is greater than their fear. They are experiencing something they’d only read about: War has come to their land. Everyone is a patriot now.

You used to scoff at that word, or argue that dissent was the highest form of patriotism. But now you find that the word expresses what you are. Now is not the moment for dissent. A couple of public intellectuals insist that it is, and you feel embarrassed for them. They quickly fade from the scene, and this serves to underscore an unprecedented sort of unity.

Nowhere is this unity more evident than in Washington. Bills are passed unanimously. These laws give new powers to the president and his security apparatus. The president, unpopular and widely considered incompetent before the attack, now steps up to direct the war effort. His demeanor—which some used to deride as primitive—is well suited for this new black-and-white era. His administration institutes sweeping surveillance to ferret out enemies at home, and wages one war and then another abroad.

American public life is profoundly transformed. The press becomes uncritical of the government. There is no outright censorship; correspondents are part of the effort now, as they were during the Second World War. American casualties pile up, the foreign carnage is enormous and unmeasured, but there is scant domestic resistance. Only at the margins of politics and the media do some people question the usefulness and legality of the war effort.

The government pushes the limits further, cutting off access to the judiciary for those deemed the enemy. The president is no longer unpopular, and he can impose his will on Washington and the country. The country is in a forever war, a state of exception that has taken away many American freedoms, some of which were ceded voluntarily.

That is what we talk about when we talk about the Reichstag fire, and it has already happened. Like sad versions of the characters in The Wizard of Oz, who set off in search of traits they already possess, we are living in fear of an event that will catapult us into a terrifying future, when the event has already occurred—and has given us our terrifying present.

The actual fire in the Reichstag—the German parliament building—burned on the evening of February 27, 1933. Adolf Hitler had been appointed chancellor four weeks earlier, and already he had begun placing restrictions on the press and expanding the powers of the police. Yet it is the fire, rather than Hitler’s toxic first steps, that is remembered as the event after which things were never the same, in Germany or in the world.

Hitler capitalized on the fire by taking an uncompromising militant stand: “There will be no mercy now. Anyone standing in our way will be cut down.” This, in turn, probably boosted his popularity, paving the way for a victory for the Nazi Party in parliamentary elections a week later.

Hitler immediately began cracking down on the political opposition. The day after the fire, the government issued a decree allowing the police to detain people without charges, on the grounds of prevention. Activists were rounded up by his paramilitary forces, the SA and the SS, and placed in camps. Less than a month later, the parliament passed an “enabling act,” creating rule by decree and establishing a state of emergency that lasted as long as the Nazis were in power.

Anschluss—the annexation of Austria—was still five years away, and the start of the Second World War six and a half, but the Reichstag fire was used to create a state of exception, as Carl Schmitt, Hitler’s favorite legal scholar, called it. In Schmitt’s terms, a state of exception arises when an emergency, a singular event, shakes up the accepted order of things. This is when the sovereign steps forward and institutes new, extralegal rules. The emergency enables a quantum leap: The sovereign has to have enough power to declare a state of exception, and then by that declaration he acquires far greater, unchecked power. That is what makes the change irreversible, and the state of exception permanent.

Every galvanizing event of the past eighty years has been compared to the Reichstag fire. On December 1, 1934, Sergei Kirov, the head of the Communist Party in Leningrad, was murdered by a lone gunman. The killer, Leonid Nikolaev, was arrested and executed, but the assassination is remembered as the pretext for creating a state of exception in Russia. Show trials and mass arrests followed, swelling the gulag with people accused of being traitors, spies, and terrorist plotters. To handle the volume, the Kremlin created troikas—three-person panels that doled out a sentence without reviewing the case, much less hearing from the defense.

More recently, Vladimir Putin has relied on a succession of catastrophic events to create irreversible exceptions. In 1999, a series of apartment bombings in Moscow and cities in southern Russia killed hundreds. This allowed Putin to proclaim that he could summarily execute those deemed “terrorists” and became a pretext for a new war in Chechnya. In 2002, the three-day siege of a Moscow theater served as a demonstration of the principle of summary execution: Russian law enforcement pumped the theater full of sleeping gas, entered the building, and shot the hostage-takers as they lay unconscious. The Kremlin also used the theater siege as a pretext to ban the already cowed media from covering anti-terrorist operations. Two years later, more than three hundred people, most of them children, died following an attack at a school in Beslan, in southern Russia. Putin used this catastrophic event to cancel the elections of local governors, effectively abolishing the country’s federal structure.

The thinking that transforms tragedy into crackdown is not foreign to the United States. During the crisis that followed the Alien and Sedition Acts at the turn of the nineteenth century, the ruling Federalists and the opposition Republicans accused each other of treason and a fatal lack of vigilance, of being Jacobin puppets. The courts, stacked with Federalist appointees, wasted no time shutting down opposition newspapers.

Half a century later, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus, the right not to be imprisoned without civilian judicial review. He did this to be able to indefinitely hold rebels whom he judged a danger to the Union—but whom, he said, “the courts, acting on ordinary rules, would discharge.” It wasn’t until 1866 that the Supreme Court ruled the practice unconstitutional.

By the next major war, the First World War, speech perceived as critical of or detrimental to the American war effort was punished with prison sentences as long as ten years. Historian Geoffrey Stone has called Woodrow Wilson’s Sedition Act of 1918 “the most repressive legislation in American history.” Thousands of people were arrested—many without a warrant—and 249 anarchist and communist activists were deported to Soviet Russia. It wasn’t until later that Supreme Court Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis started on a dissenting streak that ultimately restored and clarified free-speech protections.

The Second World War brought another presidential assault on the Constitution: the internment of more than a hundred thousand Americans of Japanese descent. Then came the McCarthy era, when the government took up spying on the enemy within and accusations of treason, whether or not they were supported by evidence, ruined life after life. The next generation of Americans lived through the secrecy, deceit, and paranoia of the Vietnam War years, which culminated in a president who had his opponents prosecuted and wiretapped. For Americans in the twentieth century a state of exception came close to being the rule.

Not all the periods of exception are remembered as repressive: In State of Exception, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben notes that Franklin Roosevelt invoked emergency powers for the passage of the New Deal in 1933, arguing that economic catastrophe warranted “broad Executive power to wage war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” Writing in 2005, Agamben drew a narrative line from the state of exception in Europe following the First World War to that in America following 9/11.

As long as war is raging, political consensus supports the crackdowns. Legal scholar Stephen Holmes calls this wisdom “the intuitive claim that grave emergencies require discretionary authority to act outside and against inherited rules and standard operating procedures.” There is no proof that such a response is effective—and there is even copious evidence that it leads to abuse of power and damage to society—but the temptation to both seize and cede power in the face of fear proves irresistible time after time.

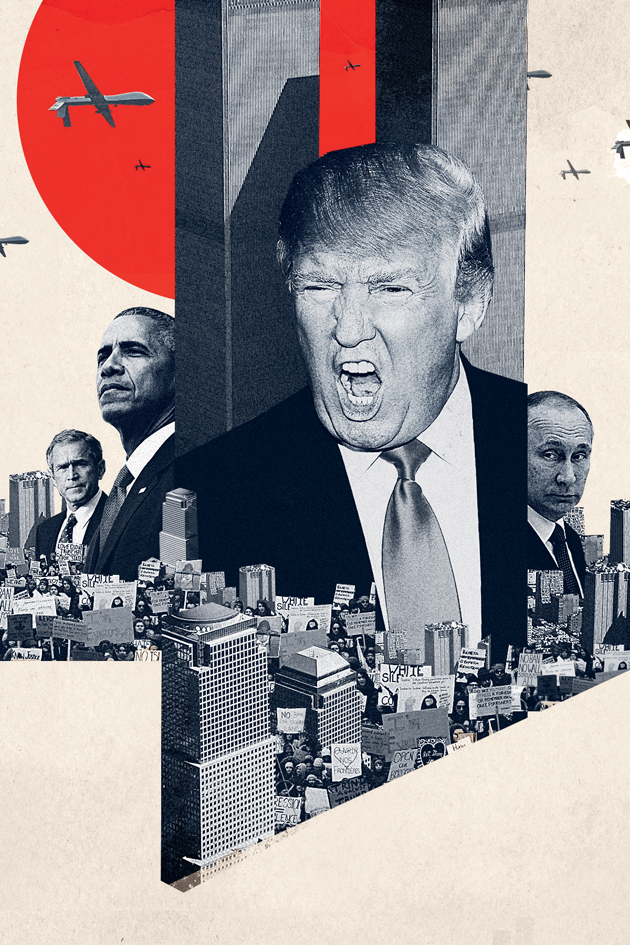

Source photographs: Donald Trump © JB Lacroix/WireImage; Vladimir Putin © Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images; Barack Obama © Ron Sachs-Pool/Getty Images; George W. Bush © Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images; protest © Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto/Getty Images; drone © Erik Simonsen/Getty Images

The war that began in 2001 is unlike other wars: The enemy is not a nation or an army but a tactic, one that has existed for millennia. This war cannot be won, because a tactic cannot be eradicated. A war that cannot be won cannot end, and so it has not. Nor have the liberties surrendered by Americans in response to 9/11 been restored. Under President Obama, the war on terror morphed into the more grammatically sensible war on terrorism. The Patriot Act became the Freedom Act. The use of torture appears to have been largely discontinued, but the camp at Guantánamo Bay continues its shameful existence—with a reduced number of inmates, though numbers are never a good measure of liberty. Millions of Americans who voted in the last election have lived with the war on terror for as long as they can remember.

In his farewell address in Chicago, Obama could claim only that he had “worked to put the fight against terrorism on a firmer legal footing. That’s why we’ve ended torture, worked to close Gitmo, reformed our laws governing surveillance to protect privacy and civil liberties. That’s why I reject discrimination against Muslim Americans,” he said, interrupted by cheers before continuing, “who are just as patriotic as we are.” Over the course of more than fifteen years, the essential premise—that the United States is at war, and that the Other in this war is Muslims—has remained unchanged. Trump claims that Muslim Americans celebrated 9/11, while Obama says that they are just as patriotic as we are; that they are not us is one of the few things the two men agree on.

The current state of exception rests in part on the national state of emergency, which George W. Bush declared three days after the September 11 attacks, which he renewed every year of his presidency, and which Obama also renewed every September of his. The president’s ability to impose and renew a state of emergency is technically limited by the 1976 National Emergencies Act, which requires Congress to vote on the state of emergency within six months of the day it is imposed. But such a vote has never occurred—even though the act has been invoked at least fifty-three times. In practice, the president wields unilateral power over emergencies.

The National Emergencies Act can be invoked for disasters beyond an actual war—Obama declared a national emergency in anticipation of the swine flu epidemic in 2009—but it invariably represents both an outsized reaction to a perceived threat and a journey outside what we maintain is normal national and social conduct. At any given time in the past decade, roughly thirty simultaneous states of emergency have been in effect. Dozens of executive orders, and numerous other directives and regulations, have stemmed from these states of emergency—all of them creating powers that would be impossible in the increasingly illusory normal state of things. A state of emergency allows the president to unilaterally seize control of the media, food supplies, and commercial vessels, for instance. The fact that Bush and Obama did not utilize some of the more extreme possibilities of the state of emergency testifies only to their restraint, not to the legal limitations. At the same time, we know less and less about the powers the government has exercised; since 2001, an ever-increasing number of these emergency powers have been classified.

The state of exception also rests on the Authorization for Use of Military Force, which was passed by Congress three days after the attacks in 2001. It gives the president sweeping power to

use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations, or persons.

The law, passed with a single dissenting vote, remains in force as the nation enters its fourth post-9/11 presidential term.

Today, when it is said that a terrorist attack is sure to happen, it is assumed that the attack will be carried out in the name of the Islamic State. The premise of inevitability is notable—one would think that such acts of terror occurred in the United States on a regular basis. Since September 11, 2001, however, there have been eleven attacks ostensibly driven by jihadist ideology; they have claimed a total of ninety-five lives. “The death toll has been quite similar to other forms of political—and even non-political—violence Americans face today,” a recent report from the New America foundation summarized. The report referred only to domestic terrorism and mass shooting incidents, but many more Americans have died at the hands of the state: In the first four months of this year, the use of deadly force by police claimed three times as many lives. These killings, extrajudicial by definition, are a symptom of the state of exception, which has turned the police into a military force. As a nation we insist on being united in fear of the one-in-millions chance of a particular kind of violence. That we seem so certain of the outlines of the Reichstag fire to come reveals the fact that it has already occurred.

Among the victims of the sixteen-year-old state of exception are hundreds of individuals identified, prosecuted, and sentenced under emergency rules. Since the war on terror began, the United States has prosecuted an average of forty terrorism cases per year, about half of them on the basis of informant operations. Convictions that result from such cases—and convictions result almost without fail, usually as the result of a plea bargain—fetch higher sentences because of something known as the terrorism adjustment in federal sentencing guidelines. The adjustment went into effect following the World Trade Center bombing of 1993 but was used most widely after 9/11. This was a law passed by Congress, yet it created an exceptional category of crime that could not be addressed by normal law. One example is the prosecution of two Iraqi refugees who were tried in Bowling Green, Kentucky, for allegedly intending to help insurgent fighters battling U.S. forces back home. The men were convicted of terrorism, even though the accusation against them—that they aided fighters confronting an army—doesn’t fit standard definitions of terrorism. They were sentenced to life in prison, in the case of a man arrested at the age of twenty-three, and forty years behind bars, for the one who cooperated with the prosecution. This was the case that Trump aide Kellyanne Conway presumably had in mind when she conjured the memory of the Bowling Green Massacre—something that never happened but, according to the logic the country has applied over the past decade and a half, could have happened.

A key characteristic of the most frightening regimes of the past hundred years is mobilization. This is what distinguishes the merely authoritarian regimes from the totalitarian ones. Authoritarians prefer their subjects passive, tending to their private lives while the authoritarian and his cronies amass wealth and power. The totalitarian wants people out in the square; he craves their adulation and devotion, their willingness to fight and die for him. Mobilization was just as important an element of Hitler’s 1933 consolidation of power as his crackdown. Victory rallies, national holidays, and parades demonstrated, even forced, the unity of a nation. In Germans into Nazis, historian Peter Fritzsche makes no mention of the Reichstag fire but devotes a chapter to the May Day parade of 1933, a daylong, citywide spectacle “carefully choreographed to .?.?. demonstrate the national sense of purpose that was now said to animate the German people.”

To totalitarianism watchers, Trump’s campaign rallies, which segued into his victory rallies, including his “America First” inauguration, have looked familiar and perhaps more worrisome than an imaginary future fire. To historians of the twenty-first century, however, they will likely look like logical steps from the years of war rhetoric that preceded them, not quantum leaps. A nation can be mobilized only if it knows its enemy and believes in its own peril.

It is not clear how many Germans attended that May Day parade because the spirit moved them and how many were compelled by fear or force. Four and a half decades later, in “The Power of the Powerless,” the Czech dissident Václav Havel described an individual who “lives within a lie,” the lie of the official ideology, without consciously accepting or rejecting it. Totalitarianism robs a person of the very ability to form an opinion.

Fear has a way of catapulting citizens into the inside of a lie. Following the apartment-building bombings of 1999, Russians huddled together, forming neighborhood patrols, eyeing strangers and neighbors alike with suspicion, and then threw their support behind the recently appointed prime minister, Vladimir Putin. In one of his first public statements, the unknown, gray little politician promised to hunt down terrorists and “rub them out in the outhouse,” rhetorically trampling the foundations of the justice system.

Americans, too, have finely honed instincts for banding together in the face of an attack. Within hours of the September 11 attacks, 150 members of Congress gathered on the Capitol steps and sang “God Bless America.” Some of them held hands. The strongest country on the planet was making a spectacle of fear and resolve. The following day, a train traveling between Boston and New York was stopped because passengers had been alarmed by the presence of a Sikh man; he was removed. Two days later, enabling legislation—bills on war powers and the state of emergency—were passed.

Trump does not have to declare war—this has already been done—or even proffer an assessment of the danger. But he has already shown that he can deftly use the coercive power of the state of being at war—this is, possibly, the only political tool of which the president has instinctive mastery. During his first address to a joint session of Congress, Trump orchestrated more than two minutes of applause for the widow of a fallen Navy SEAL. It was 125 seconds of naked cynicism that left no one in the audience any choice but to stand and applaud. The following day Breitbart falsely claimed that several top Democrats had refused to do so. This was a preview of the coercion by national unity that we talk about when we talk about the Reichstag fire, but it was also reminiscent of the early weeks and months following 9/11, when Bill Maher and Susan Sontag were shamed for breaking rhetorical ranks.

In Russia, it took many years for Putin to consolidate power, and it wasn’t until 2012 that his regime assumed its current retro-totalitarian character. Over the years, the use of terrorist attacks to justify successive crackdowns has grown familiar and gradually transformed the country’s thinking. The lack of logical connections between events and their ostensible consequences, along with the general degradation of the judicial system and law enforcement, eroded all trust in the government—to the extent that every time a terrorist attack occurred, many Russians assumed that the government, no matter what it said, was behind it. When a bomb went off in the St. Petersburg Metro in April, killing fourteen people, journalists and Russia watchers instantly assumed that the Kremlin had organized the attack in order to detract attention from or to stifle emergent anti-corruption protests.

Over the years many Russians, including me, have come to believe that the apartment-building bombings in Moscow and elsewhere were organized and carried out by the FSB, the intelligence agency, in order to shore up Putin’s power grab. There has never been a transparent and satisfying investigation of the blasts, but the available evidence stacks up in favor of this theory.

When we talk about the Reichstag fire, we speak not only about an event that precipitates a state of exception and launches coercive national mobilization but also of a conspiracy. Many Germans were certain that the Reichstag fire was set by the Nazis themselves. So much evidence supported this theory that for decades after the Second World War a Nazi conspiracy was the historians’ consensus. During the same period, it was generally accepted that the Kirov murder was a secret-police assassination. But when all the available information on the Kirov murder was excavated in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was no proof to back up the conspiracy theory: It is now believed that Kirov was killed by his assistant’s jealous husband. In the 1960s, reporting cast doubt on the theory that the Nazis burned down the Reichstag, but in the 1990s, a new wave of evidence suggested they may have been involved after all. Historians continue to debate the issue. (A young Dutch Communist was apprehended at the scene, tried, and sentenced to death by beheading.) It is certainly too early to exonerate Putin and the FSB for the apartment bombings, but the Russian autocrat may eventually be proved to have simply seized an opportunity, as he has done many times since. For now, though, we do not know enough, and this paucity of information, too, is one of the signs of an autocracy.

Autocracies thrive on and engender fear, ignorance, and—their combined product—conspiracy theory. Writing in his diary in January 1934, the linguist Victor Klemperer assessed a genre of joke. “Conversations in heaven are popular. The best one: Hitler to Moses: But you can tell me in confidence, Herr Moses. Is it not true that you set the bush on fire yourself?” The joke shows Hitler and the satirist sharing a conspiratorial worldview: The person telling the joke believes that the führer set the Reichstag fire and also that Hitler sees the world through the lens of his own deception. Everyone is both a conspirator and a conspiracy theorist.

The September 11 attacks, like all unimaginable events, spawned conspiracy theories. Trutherism spread far and wide; its younger cousin, birtherism, grabbed hold of a smaller but more vocal constituency. By the time Trump was elected president, America was living through an epidemic of conspiracy thinking. Some were convinced that Hillary Clinton ran a child-sex ring from a pizza shop in Washington; others that every recently dead Russian man was connected to Trump’s election victory. No one now seems to believe that most things are what they seem: usually, a mess.

When we talk about the Reichstag fire, we talk about the consequences of a catastrophic event. But in our case, these consequences—a legal state of exception, a sense of living under siege, popular mobilization, and an epidemic of conspiracy thinking—are already in place. Indeed, they are the preconditions of our current predicament. Trump used the conspiracy thinking and the siege mentality to get himself elected. Once president, he used the state of exception to begin lobbing missiles, dropping bombs—nothing less than the so-called Mother of All Bombs. Mobilization, the popular sense of being together in constant battle, ensured that Trump’s first forays into war looked good on TV. At the same time, Trump overestimated the power given to him by the siege mentality. When he attempted to ban Muslims from entering the United States, for example, he encountered great popular and institutional resistance.

Here lies our best hope for reversing the effects of the next Reichstag fire: American civil society is strong—far stronger, paradoxically, than it was before the election. And something remains of what Hannah Arendt observed in a letter from 1946:

People here feel themselves responsible for public life to an extent I have never seen in any European country. For example, when all Americans of Japanese descent were locked up willy-nilly in concentration camps at the beginning of the war, a genuine storm of protest that can still be felt today went through the country.

What struck Arendt was the spontaneous and active expression of solidarity on the part of ordinary Americans who “declared that if something like that could happen, they no longer felt safe themselves.”

The comparison to contemporary protests may not be entirely straightforward. Leading arguments rested on the impossibility of religious discrimination; popular protest relied on a general sense of injustice and the rational argument that banning the entry of people from seven majority-Muslim countries would do little to protect Americans from terrorism. But by pointing to the ineffectiveness of the proposed ban, some of these arguments unwittingly reinforced the idea that Americans can make themselves safer by shutting out some part of the world.

Most recent protests share a fundamental flaw: They project the assumption that things were fine until America inexplicably elected Trump. The women’s marches, the immigrants’ marches, the scientists’ marches, the protests in defense of the Affordable Care Act and freedom of speech, and the earliest of the protests, which simply expressed outraged disbelief at the results of the election, all serve the purpose of staking out the current norms and vowing to defend them. It’s hard to argue with the urge; all indications are that the current norms are far preferable to the reality of the near and distant future. Yet most of the protests live within a lie—the fiction that the threats of the Trump presidency are not only grave but also new. His war against the national press is a grotesque blowup of many years’ worth of growing regimentation of access, concentration of power, and government opacity. Trump’s war on immigrants builds on the mass deportations of the Obama years, which were themselves built on the siege mentality of the Bush years. Trump’s casual bomb-throwing is enabled by the forever war begun nearly sixteen years ago.

To confront the threat we face, it is not enough to advance the rational argument that an American has a lesser chance of dying in a terrorist attack carried out by a refugee than of being struck by lightning. Nor is it enough to focus on the grave injustice of tarnishing immigrants as potential criminals and Muslim refugees as potential terrorists. It is most certainly not enough to revel in the beauty, intelligence, and wit of the many people who have come out to protest Trump’s attacks on humanity and its planet. There is, in fact, no room for self-congratulation in the actions we need to take.

To be worthy of the lofty name “resistance,” the opposition to Trump must aim to break the country’s post-9/11 trajectory. It must question the very premise of the war on terror, challenge the very fact of a perpetual state of emergency, and confront not only the Trump presidency but the legacy of the Bush and Obama Administrations. Organizations such as the A.C.L.U. have been doing this for years. The Trump presidency has not only, paradoxically, brought the group millions of dollars, it has also, potentially, rallied millions of people to the cause. Now is the time to stop waiting for the Reichstag fire and start battling the consequences of the one we already had—Trump and the legal and public conditions that are enabling his presidency.